11 MAY 2006 - JUAN FORERO

|

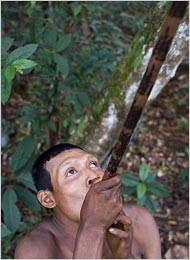

SAN JOSÉ DEL GUAVIARE, Colombia — Since time immemorial the Nukak-Makú have lived a Stone Age life, roaming across hundreds of miles of isolated and pristine Amazon jungle, killing monkeys with blowguns and scouring the forest floor for berries.

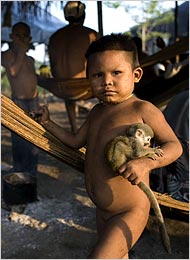

But recently, and rather mysteriously, a group of nearly 80 wandered out of the wilderness, half-naked, a gaggle of children and pet monkeys in tow, and declared themselves ready to join the modern world.

"We do not want to go back," explained one man, who uses the sole name Ma-be, and who arrived with the others at this outpost in southern Colombia in March. "We want to stay near town. We can plant our own food. In the meantime the town can help us."

While it is not known for sure why they left the jungle, what is abundantly clear is that the Nukak's experience as nomads and hunter-gatherers has left them wholly unprepared for the world they have just entered.

The Nukak have no concept of money, of property, of the role of government, or even of the existence of a country called Colombia. They ask whether the planes that fly overhead are moving on some sort of invisible road.

They have no government identification cards, making them nonentities to Colombia's bureaucracy.

"The Nukak don't know what they've gotten themselves into," said Dr. Javier Maldonado, 27, a physician who has been working with them.

When asked if the Nukak were concerned about the future, Belisario, the only one in the group who had been to the outside world before and spoke Spanish, seemed perplexed, less by the word than by the concept. "The future," he said, "what's that?" He serves as a interpreter for the others. One of perhaps a few dozen indigenous communities living in relative seclusion in the Amazon basin, the Nukak have, in dribs and drabs, gone beyond the borders of their jungle world only since 1988, just as the world has intermittently found them.

In 2003 dozens of Nukak left the wilderness and arrived at San José del Guaviare, saying Colombia's relentless civil war had encroached on their reserve and forced them to seek safety. Perhaps as many as 250 now live in settlements around the town, about as many as anthropologists suspect are still alive in the wilderness.

In recent years Nukak clans in the jungle have also had some contact with missionaries and with farmers and sedentary indigenous groups, who trade their crops for meat hunted by the Nukak, who picked up at least the notion of agriculture.

Though it is unclear how big the Nukak population once was, anthropologists believe that what little contact the Nukak have had with outsiders has most likely left them reduced by Western diseases, including influenza and the common cold, to which they have no natural defenses.

Janet Chernela, an anthropologist who has worked with the Nukak, said a study she had conducted showed that Nukak who abandon their nomadic lives and settle down, even temporarily, become susceptible to illnesses, including soil-transmitted diseases.

What little is known about this latest group is that it abandoned the Nukak National Park, which is nearly half the size of New Jersey, in the state of Guaviare. Belisario — who knows several of the towns outside the reserve, having been reared for part of his childhood by settlers who encroached on the jungle — led the way.

It was no easy journey, the Nukak told Dr. Maldonado, spanning nearly 200 miles from the eastern end of their reserve to this town, known locally as San José. They arrived in the central plaza malnourished and exhausted, as astonished by this world of low-slung jungle buildings, jeeps and paved roads as the townspeople here were astonished by them.

"When I've had some time to talk to them and asked where they came from, they just say 'the bush,' " said Xismena Martínez, who oversees aid to the Nukak for San José. "But that could mean anywhere."

The newly arrived Nukak do not provide much detail about why they left. They just say that "the Green Nukak," a possible reference to Marxist guerrillas, who wear camouflage, told them to leave.

"The Green Nukak said we could not keep walking in the jungle, or else there would be problems," explained Va-di, another Nukak man, whose words were translated from Nukak by Belisario. "The Green Nukak told us to go where it is safe."

Colombian officials wonder if farmers growing coca, the crop used to make cocaine, may also have displaced the Nukak, who are peaceloving and unlikely to fight. Another theory is that another Nukak clan pushed this one out.

But because it is assumed that they fled the civil war, the Nukak are classified as displaced people, requiring the state to provide aid and help them return home, as long as it is safe. The government, though, cannot guarantee their safety.

Nor can officials force them to go back. So the town and the government are providing them food and clothing in a forest clearing called Aguabonita outside San José.

"We can't say, 'You're a Nukak, go back to the bush,' " said Ramón Rodríguez, who is overseeing assistance efforts from the central government's emergency aid organization, Social Action.

But even as the aid arrives, the donors are well aware that the largess could well doom the Nukak to a life of dependency, ensuring not only that they never return home but also that they never learn how to live in their new world.

"People want to protect them," Ms. Martínez said. "To help them, we give them food and clothes. That doesn't help them at all in the long term."

What everyone agrees on is that the Nukak of Aguabonita must avoid the fate of the Nukak who came here in 2003 and now live in a clearing called Barrancón.

Now in their fourth year in the area, the Nukak in Barrancón lead listless lives, lolling in their hammocks awaiting food from the state. They do not work, nor have they learned Spanish. They also have no plans to return to the forest. "I think we will be here always," said Martín, a young man who is considered a leader.

In Aguabonita, the scene on a recent day was full of commotion and laughter. Naked children tugged at the shirts of two foreign journalists, offering big smiles and hugs. The men quickly welcomed the visitors into a makeshift shelter, where they laughed at some of the questions and, it seemed, wholly innocently at their own odd predicament.

Are they sad? "No!" cried a Nukak named Pia-pe, to howls of laughter. In fact, the Nukak said they could not be happier. Used to long marches in search of food, they are amazed that strangers would bring them sustenance — free.

What do they like most? "Pots, pants, shoes, caps," said Mau-ro, a young man who went to a shelter to speak to two visitors.

Ma-be added, "Rice, sugar, oil, flour." Others said they loved skillets. Also high on the list were eggs and onions, matches and soap and certain other of life's necessities.

"I like the women very much," Pia-pe said, to raucous laughs.

One young Nukak mother, Bachanede, breast-feeding her infant as she talked, said she was happy just to stay still. "When you walk in the jungle," she said, "your feet hurt a lot."

The men still go into the jungle, searching for monkeys, a delicacy the Nukak cannot seem to live without. Monkeys are grilled, dismembered and boiled, then eaten piece by piece. The women still spend their time carefully weaving intricate wristbands and hammocks, using threads from palm leaves.

All live in shelters now, enjoy constant medical attention and, on weekends, stroll into town to take in the sights. "Nukak life is hard in the jungle," Dr. Maldonado said. "You wake up thinking about food and you go hunt, you go search for nuts. So when they see us they think their food problems are over."

That is not to say the Nukak do not have plans.

Ma-be explained that the idea is to grow plantains and yucca and take the crops to town. "We can exchange it for money," he said, "and exchange the money for other things."

But first they need to learn how to cultivate crops. The Nukak say they would like their children to go to school. They also say they do not want to lose traditions, like hunting or speaking their language. "We do want to join the white family," Pia-pe said, speaking of Colombian society, "but we do not want to forget words of the Nukak."

After a recent meeting with government officials, the Nukak were clear about what else they wanted: vehicles, drivers and doctors so a group of 15 Nukak could set off on a tour of the countryside, searching for a spot to settle down.

They do not ask for much — land to plant, preferably close to a town but also on the edge of a forest. They do not want armed men around, nor coca, they say.

"They will look to see if there are nuts, monkeys, water," said Ms. Rodríguez, the town official handling the latest request. "If they find it, then, yes, that's the spot."

http://www.entheology.org/