March 24, 2008 - San Francisco Gate

|

By David Ian Miller

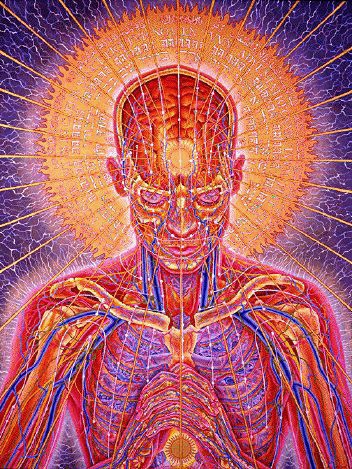

Alex Grey paints souls. His work shows human bodies — rendered with medical-illustration precision — wrapped in layers of sacred energy. Whether you believe Grey's work depicts the reality of divine auras or a particularly vibrant artistic license doesn't much matter. His paintings have an uncanny effect on viewers, making them sense — or at least consider the possibility of — the subtle energies that surround us and how these personal force fields might change depending on our intention, actions and moods. They are modern-day religious icons and mandalas for 21st century Westerners.

Grey, 55, lives and works in New York City with his wife, the painter Allyson Grey, and their daughter, actress Zena Grey. The Greys host regular full and new moon all-faiths-welcome gatherings at their Chapel of Sacred Mirrors, a sanctuary and art gallery where selected paintings of Grey's are on permanent display. I spoke to him by phone about art's power to transform, Tibetan Buddhism and the danger of chasing many rabbits but catching none.

SFG: In an essay of yours called "What Is Visionary Art?" you wrote that the artist's mission is to make the soul perceptible. How do you do that, if you can put that into words?

AG: I think that that's why artists make art — it is difficult to put into words unless you are a poet. What it takes is being open to the flow of universal creativity. The Zen artists knew this. Their edict was, in order to paint the mountain you must become the mountain. That's one way to make the soul perceptible, when one mirrors something and then expresses it from that perspective. Then there are what I think of as gifts of the divine imagination, when one can gain a glimpse into the visionary realm. Some of these visions are so intense that they burn themselves into your neuronal fabric. And so you remember them, and then you make a drawing or, if it was an auditory thing, you write down or hum or do whatever the musician does.

SFG: You had a kind of vision as a young man that changed your life and work. Can you tell me about that?

AG: It was 1975. I had spent the year at the Boston Museum School doing some very bizarre performance works. The last one included going to the North Magnetic Pole and spending all of my money. I came back exhilarated and exhausted, not to mention slightly suicidal. I was pretty young, like 21. I'd been searching, and I just didn't understand what my life was all about. So at one point I kind of asked, "If there is a God, then please give me a sign."

Then, on the last day of art school, I was standing on a street corner, saying goodbye to my professor, when this woman drove by and invited us to a party later that night. My professor picked me up that evening and offered me a bottle of Kahlua and LSD, and since I felt like I had nothing to lose — I had never done psychedelics before — I tried it. I drank about half the bottle. And when we got to the front door of the lady giving the party, I told her what was in the bottle, and she drank the rest of it. I went into her apartment, sat on a couch and closed my eyes; inside of my head it seemed like everything was in a big, dark tunnel, but I was revolving around in a spiral toward the light. There was this beautiful, amazing kind of luminosity, a kind of light that I'd never imagined. It was the light of love, the light of redemption, in a weird way. I felt a kind of ecstatic joyfulness that was a real release from my depression, and I saw the experience as symbolically important in that I was in the dark, going toward the light.

SFG: This was a kind of spiritual awakening for you?

AG: Exactly. It was like going through a spiritual rebirth canal. And it was like nothing I had experienced before. I called the girl (the party giver) the next day, and asked if we could get together and talk about the experience. She ended up being my wife, 33 years ago. So it was a definite turning point. I had met a sort of divine love in the flesh in the form of my wife, and this definitely opened me up to a new realm.

SFG: How did this change your art?

AG: Well, it kind of monkey-wrenched everything, to begin with. I became really interested in the study of consciousness. I started making drawings about what I'd seen, and we continued to explore with psychedelics.

On one occasion of doing that — we would take a dose of LSD, lay in bed with blindfolds on and listen to Bach organ music — we went into a space that we called the "universal mind lattice." In this state, our identity with the physical body melted down into a kind of fountain and a ball of light that was connected with an infinite expanse of very similar balls of light; it seemed like the same kind of energy was running through all of us, and every other being and thing in the universe was one of these balls of light, infinite and omni-directional. It was a perspective that seemed outside of time, somehow. It made me start to search in mystical literature for descriptions of similar experiences. And it inspired us to make art about infinite interconnectedness or unity, which became the criterion for our work.

SFG: When did you first have the idea of creating a sacred space for people to view your art?

AG: My wife and I had a kind of simultaneous vision while we were having our first MDMA experience. We both saw ourselves walking through this kind of futuristic chapel, a kind of sacred space. At that point we had the realization that we should not sell our artwork but instead create a new kind of sacred space to house it. That became almost like an edict. Of course, as artists, it's hard enough to make a living selling your art, but if you keep your work in order to house it in a sacred space, then you are creating extra challenges. But that was our inspiration at the time. We wanted to build a new kind of sacred space.

SFG: What did you build?

AG: Our dream was to create a Chapel of Sacred Mirrors. The Sacred Mirrors are a series of paintings that I created. Allyson inspired them and named them, but I painted them over a 10-year period. And we've added a number of other works to the collection — there are about 50 pieces right now, including works by other artists.

SFG: What kinds of experiences do people have there?

AG: Sometimes the artwork has validated a visionary experience that people have had. Another function has been a kind of adjunct to people's healing. The Mirrors (represent) healthy, whole systems of the anatomy, and people can stand in front of them and mirror what they are seeing. There have been people who have had heart problems and things like that who have used them in this way.

We have a lot of spiritual teachers who have come there and taught, but our primary goal is to inspire people to unite their creative and spiritual lives, and to create their own kind of sacred art. A number of people do video work, and there have also been dance performances. It's become like a cultural center, but with the particular slant of a kind of visionary culture.

The creative principle is less about dogma and more about opening ourselves to the evolution of consciousness. It's always been a part of our understanding of God. God is the creator. God is the, "Behold, I make all things new." The more religions are fixated on having a dogmatic sense of truth, the more likely they are to blow each other up. So being open to God as a creative principle could provide for a new kind of dialogue between the faiths, which I think is crucial at this time.

SFG: What happens at the full moon ceremonies?

AG: My wife describes them as a kind of interfaith variety show. We have an imam for the New York correctional system, a wonderful fellow named Dawoud Kringle, who plays his sitar and gives teachings based on Islam and Sufism. My wife covers the Jewish beat, and she goes over the Parsha (Torah passage) for that week, and I frequently will give a Christian or a kind of offbeat creative poetic kind of reflection.

SFG: You advocate a kind of inclusiveness towards the world faiths. Is there a particular tradition that you are most aligned with?

AG: I was talking to my friend, Ken Wilbur, about how much I loved all the different traditions — Kabbalah has this wonderful tree (of life), the mystic Christians have their particular practices that are really wonderful, and the Sufis — oh my God, what an amazing approach to the divine! And he said, "Alex, chase many rabbits. Catch none." Basically, choose one and go with it for a while. And so, with that kind of admonition, I wound up choosing Tibetan Buddhism as my path.

SFG: Why did you choose Tibetan Buddhism?

AG: I think that in the wake of my psychedelic experiences it was the approach that more closely modeled the multidimensional experiences that I was having, and it talked about a kind of hierarchy of beings, very similar to the sort of celestials that you can find in the Christian tradition or in the kabbalistic or the Sufi tradition, but they were very specific. They had names. You could work with them. You could invite them into your own being. And it was after reading (Tibetan Buddhist book) "Self-Liberation Through Seeing with Naked Awareness" that I just absolutely fell in love with Tibetan Buddhism, and I had a strong visionary experience without any kind of drug influence.

SFG: Do you still do drugs?

AG: Well, actually, I haven't for quite a while.

SFG: Why not?

AG: I think part of it has been the responsibility of being a kind of leader of our community in the chapel. So basically, my wife and I are doing more meditation and yoga — more standard spiritual practices — and doing our artwork. We have not felt the need or the desire for the substances, even though I feel like they should be regarded as sacraments, and there should be a place in our society for making use of their powerful ability to open people up to the visionary realm.

SFG: What are the artistic challenges in translating inner worlds or the realm of the soul to a canvas?

AG: The first challenge is to have an authentic mystical experience. That's not such an easy thing to have happen, and it can happen in a variety of ways.

SFG: How do you know that you have an authentic mystical experience?

AG: I think that's kind of self-revealing. You know, when you see the face of God, or when you have an overwhelming, ecstatic, blissful, visionary experience, there is no doubt about it. It isn't like: "Did it happen?" It's unforgettable. And you are a changed person in some way. I wish there were a word for the ecstatic blissful liberation, but when you have a glimpse of it you know what the mystics are talking about. Except they are talking about a life lived in the light of that.

SFG: And then translating that into art?

AG: That's the challenge! So frequently the visions are very dynamic, they change. But then there is a sense, with some of them, where you are in a place that is very recognizable. It has a form. And so you basically come back and start drawing it. Both my wife and I make notations as quickly as possible after experiencing the state. You notice if there were colors involved or what kind of shapes there were or what kind of light was there. And then you make these little sketches ... and that's the best I can really say. But many people have had these experiences. It is just difficult to portray them.

SFG: Difficult to portray and perhaps difficult to relate to if you haven't had the experience?

AG: Absolutely. For some people, maybe my artwork just seems like fantasy or something. However, if you have had any kind of a mystical or cosmic experience, I guess, then people seem to recognize the territory.

SFG: In an interview from some years back, you were talking about your "inner wienie," which tells you what you can't do, versus "the primordial that flows through all of us and that "with it, everything is possible." Can we talk a little bit more about that? How do you quiet the inner wienie and connect with the primordial?

AG: That's funny. That language isn't what I'd use today, but it's probably an apt description of the kind of cowering ego before the forces of the world. I think that basically you commit to what your imagined highest possibility is and to being as loving and straightforward in your relationships as possible. You also have to listen very deeply and look to see what you are being guided towards. You can't always be super clear about these things. It can be very challenging. I mean, it is for me.

SFG: Is "the primordial" God or something else?

AG: I use a lot of different words for God — infinite intelligence, primordial, perfection or universal creativity. All of these, to me, are God. And God is a word, I think, that some people feel uncomfortable with, so they can use another word, you know? It's the great mystery. And it's the core of our being. And it's the greatest expanse of everything in the cosmos. God's inexplicable. God is beyond the everything. And yet we can't cease to blather about it.

http://www.entheology.org/