Tuesday, December 09, 2008 - by Linda Loca

|

In celebration of the lifting of the almost 100-year ban on absinthe, what follows is an overview of the elixir’s history. We will share recipes with you, as well as the best places we have found to purchase ready-made absinthe, absinthe kits, as well as individual ingredients. Discover why this drink has become so infamous the world-over, and was the favorite of so many artists throughout history.

Absinthe, otherwise most popularly known as The Green Fairy, was colloquially referred to as the “national drink” of France during the period from the end of the Franco-Prussian War to the beginning of World War I. This fashionable elixir, renown for its chartreuse color, bitter taste and anise flavoring, was all the rage during this period of Western Europe’s history, when the region was experiencing relative peace and prosperity, and the art world was flourishing.

Absinthe served as inspiration for many literary and visual works of art. Both Toulouse-Lautrec and Edouard Manet immortalized the liqueur in their paintings. Writers Oscar Wilde and Ernest Hemingway were both influenced by the “the green goddess” (another popular name for the drug). The work of Vincent van Gogh, an absinthe addict, still serves as visual representation of the hallucinogenic effects of absinthe through his use of hyper-real color and vibrating, highly textured views of reality.

Outlawed in France in 1915, absinthe left behind a spectacular narrative of a heady time, with colorful, artistic luminaries dotting the landscape of its rich history such as Pablo Picasso, whose use of distorted and heightened color reflects the effects of absinthe - and Paul Gauguin, whose Tahitian period was said to have been highly influenced by the plentiful supply of “the green muse” that he brought with him on his travels to Tahiti. In Gauguin’s painting At the Café/Night Café, one can clearly see an absinthe glass with a spoon in it, some sugar cubes on a tray and water bottle sitting on the table in front of a woman with a blissful, dreamy look on her face, her skin tinged with the color green, all obvious references to absinthe and its effects.

Traditionally distilled from a variety of plant extracts infused into an ethanol base, the exact recipe for this “ambrosial poison” (yet another metaphor for absinthe during the early 20th century), varied from one maker to another. The main flavoring agent was consistently wormwood (Artesmia absinthium) – in French, grande absinthe (large wormwood) – which gave la fée verte (French for “the green fairy”), its characteristic bitterness.

The word absinthe comes from the Greek word apsinthion, meaning undrinkable, most likely referring to its bitterness. In better-quality absinthe, less acrid Roman wormwood (Artesmia pontica) – in French, petite absinthe (small wormwood) – was also used to soften the bitterness. It has been said that the best absinthe is refreshingly, not overwhelmingly, bitter.

Green anise (Pimpinella anisum) and fennel (Foeniculum vulgare) produced the anise-like taste, and the chlorophyll of hyssop (Hyssopus officinalis) and lemon balm (Melissa officinalis) gave “the melted emerald” (another absinthe nickname), its signature green color.

The finest absinthe uses twice-distilled alcohol made from grapes as opposed to grain. Production is broken down into three stages: basic ingredients are macerated in alcohol and water, then distilled. The distillate is then macerated with coloring agents, then barrel aged. Lesser quality absinthe is made by adding plant extracts to lower grade alcohol. The liqueur was released in various grades from ordinaire to extré-superieure, with the alcohol content ranging from 45 to 75 percent.

The extract of wormwood has been used since ancient times as a medicine for a variety of ailments, but its chief medical application has been to purge intestinal ringworms. The history of absinthe as a beverage started in French-speaking Switzerland in the eighteenth century. Exactly who first began making it is highly disputed.

Non-substantiated rumor has it that a French physician in the Swiss village of Couvet prescribed absinthe as a cure-all tonic. Another resident of Couvet, Henriette Henriod, is documented to have made several home remedies from her garden-grown wormwood; she very well may have been the first person to make absinthe by distillation rather than by infusion.

Word of the inebriating effects of “the parrot” (a less popular, yet noted metaphor of absinthe), spread rampantly. To capitalize on the product’s non-therapeutic properties, Henri Louis Pernod and a group of investors acquired the recipe and opened a small absinthe factory in Couvet in 1797. In order to avoid paying import taxes, Pernod opened a larger facility named Pernod FIls in 1805 in Pontarlier, a few miles across the Swiss border into France.

In the beginning, many if not most absinthe drinkers were so attracted to the bitter taste that they took their absinthe unsweetened and undiluted. Later, however, changing tastes and pressure from temperance advocates dictated that absinthe be diluted with water, and preferably be sweetened. Served in simple glasses, water was poured into the liqueur from a simple carafe or other such decanter. Most likely the first method employed was to lay a fork across the top of a glass containing absinthe, place a sugar cube on the tines, and slowly pour water over the cube into the glass.

The effects of the addition of water - namely the separation of essential oils from the alcohol base, which released the aroma of anise and changed the liquid from a clear green to a milky sage – assumed a ritualistic significance, and it became an important control in the diluting and sweetening process. Various devices specially designed for this process started to appear as early as the late 1800s; the most simple and long-lasting of which was the absinthe spoon – in French, cuillére á absinthe.

As the popularity of absinthe grew, along with its lore as semi-sacred ritual beyond mere drink, so too did the variety of implements to accompany the beverage. These included specialty glasses that replaced normal bar-ware, with short, thick stems and faceting to increase the formality and uniqueness of the experience.

The ritual for genteel preparation was as follows: A dose, or serving, of about one to one-and-one-half ounces of absinthe was poured into a footed, faceted glass. The absinthe spoon was laid across the top of the glass and a sugar cube was placed on it. Chilled water was slowly poured onto the cube, which then dissolved into the glass. The usual dilution was four to six parts water to one part absinthe.

The footed glasses varied in size, from about 5½ to 7½ inches in height, and were made of heavy gauge glass to withstand rough use. They were either generic or specifically intended for absinthe. The latter had marks on the sides to indicate the standard serving of absinthe, or had a special “reservoir” in the bottom to hold the proper amount. When not dispensed into a glass, absinthe was sometimes served from small glass decanters known as topettes usually topped with a glass bouchon, or stopper. Many topettes had marks or designs that delineated a standard serving. Absinthe was also manufactured in mignonettes, comparable to the one-drink miniatures from which spirits are dispensed on airlines today.

Some of the oldest examples of absinthe spoons date from the middle of the nineteenth century and are still manufactured today. The most common, traditional absinthe spoon is trowel-shaped and flat, with a slightly raised back wall so that the liquid doesn’t flow over the end of the spoon, and with a notch in the handle so it can rest on the rim of the glass. The spoon is slotted to allow the water poured over the sugar cube to drain freely into the absinthe below. At the height of the drink's popularity, absinthe spoons were often regarded as novelty items, and came in such touristy shapes as the Eiffel Tower.

The "Les Cuilleres" spoon is the most rare variation on the absinthe spoon. Resembling the form of an iced-tea spoon, these have a normal spoon bowl with a lattice-work, ornately designed sugar holder built into their long, slender handle.

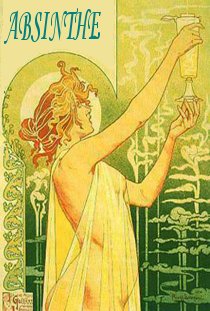

The popularity of absinthe was encouraged by an aggressive marketing strategy on the part of the distillers. They commissioned posters that bore their distillery name and then gave these to cafes. They also often supplied cafés with items displaying their brand name, including serving glasses, spoons, decanters, water carafes, clocks, ashtrays, and match holders/strikers, most of which are highly collectible today and some are very rare and hard to find.

Now that the ban on absinthe has been lifted in the United States, as well as around the rest of the world, all of us now are able to enjoy The Green Fairy again in all her glory.

http://www.entheology.org/